MISTAKE # 2: IGNORING INSCRIPTIONS

-False Attribution

Ignoring inscriptions on a painting is a mistake. It would block you from verifying the authenticity of a painting. Most traditional Chinese paintings contain words and images. Inscriptions are divided into two categories: primary and secondary. Primary inscriptions include the title of the painting and the artist’s signature, a related poem, or lines on the circumstances inspiring the painting, such as location, time of year, specific day, seasonal events, and the person to whom the painting is gifted, written by the artist. Secondary inscriptions refer to other words on paintings, such as opinions of later connoisseurs-who (of course!) tend to love the paintings they collect. Inscriptions on a painting tells a story.

Understand the story and judge its quality and truthfulness by asking some questions. Are the dates correct? Do the nicknames match those used by the artist during this period? Do the geographical references and other languages fit the time and place?

MISTAKE #3: FAILING TO RANK OVERALL QUALITY

-Inadequate Quality Assessment

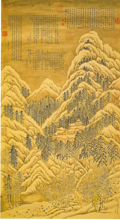

Depending only on the signature and seals on a classical Chinese painting to shed light on marketability is a mistake. Instead, an objective overall quality assessment of the painting supports the reliability of value conclusion. A mediocre work by a great artist would obviously be lower in value than an excellent work by the same artist. But how do you judge quality, compare, say, an inspired work by a second-class artist to a perfunctory work by a famous artist?

Possessing some knowledge of Chinese traditional standards of aesthetic judgment, such as ranking painters and paintings, evaluating brushwork, iconography, and biographic basis of an artist’s style, is essential. Drawing on modern criteria in judging overall quality, such as dynastic style and personal style, publication history, celebrity ownership, provenance, and sales history is a necessity in the appraisal of classical Chinese painting.

A balanced judgment of the overall quality of a classical Chinese painting functions much like an algorithm in ranking and weighing the significance of a different value features.

MISTAKE #4: USING UNQUALIFIED COMPARABLES

-Relevance Issue

Using a consistent, objective method to weigh the overall quality of artwork forms a solid foundation for finding qualified comparables. For traditional Chinese paintings, further questions include the most appropriate marketplace, sales venue, and the condition of the art market at time of sale (market economics, trends in general? For the artist, genre, or period?)

It is mistaken to use the “apples to oranges” or “fresh apples to rotten apples” method to qualify comparables in the appraisal of classical Chinese painting.

MISTAKE #5: CLOAKING VALUE ADJUSTMENTS

-Unjustified Value Conclusion

If you don’t explain in words that data provided in your report and why it is arranged the way it is, you won’t establish your value conclusion. Even strong reports-based on good knowledge of Chinese aesthetics, offering appropriate ranking of a painting’s quality-can fail at this crucial step.

Failing to provide a narrative that conveys the appraiser’s reasoning process in weighing and ranking differences between qualified comparables is a mistake.